The Creative Problem-Solving Clock

Six simple steps toward sanity

|

|

1

2

3 4

5

6

7

8

9

10

The Clock

Back to Top |

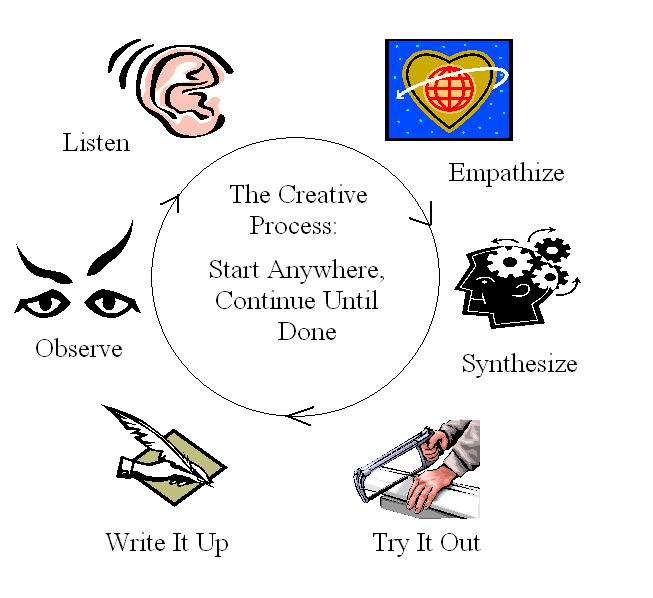

Problem solving is a creative process. Here is a framework

for getting results in a repeatable, predictable way.

The process is illustrated below. It is

an iterative approach. I describe the picture in more detail in the

sections that follow.

|

|

I solve problems by going around the circle at least twice,

and more than that if required. In the real world, it is possible to begin

the process at almost any point on the circle, but for convenience I

begin my explanation at the most “logical” place, nine o’clock. And I'll

switch from "I" to "we" because we are going to do this together!

The first time we go through the loop, the steps are a

little different from those on subsequent trips.

|

1 2

3 4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Getting Started

Back to Top |

|

1

2 3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Observe

Back to Top |

|

|

Nine o’clock: We need to be

aware. We have to have our antennae out all the time. We

aggressively watch what is going on around us, and we try to sniff out

problems. |

|

|

|

Eleven o’clock: Having detected a problem, we engage

with others to find out what they think. We use active listening,

creating a Socratic dialog with our conversational partner, alternating

teacher and student roles. We try to listen more than we talk, and we

take good notes. |

|

|

1

2

3 4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Listen

Back to Top |

|

1

2

3 4 5

6

7

8

9

10

Empathize

Back to Top |

|

|

One o’clock: I separate this from listening to make

sure that you understand the difference. One can listen to get "objective"

data; empathy is the bridge between listening in the fact-gathering sense

and the beginning of the synthesis part of the process. We listen with our

ears and synthesize with our brains; empathy involves use of the heart. It

requires that we step outside ourselves and truly put ourselves in the other

person's shoes. This is not always easy to do when what we are hearing does

not agree with our previous notions. Hence we must empathize before we can

synthesize. Managers who come from engineering sometimes skip this step because

they are used to solving problems that are 99.44% technical in nature;

unfortunately, this is not the case with most general management problems. |

|

|

|

Three o’clock: Here we bring together all the pieces:

-

The data we have

gathered through observing and listening

-

The affective

elements discovered by seeing it from other people’s perspective

-

All our previous

experience in dealing with problems of this type

-

Other “lateral”

experience that may be relevant

-

Our “tool bag” of

methods, processes, strategies, tactics, techniques, and tricks

We fabricate a

trial solution to the problem, using everything we know. |

|

|

1

2

3 4

5 6

7

8

9

10

Synthesize

Back to Top |

|

1

2

3 4

5

6 7

8

9

10

Try It Out

Back to Top |

|

|

Five o’clock: In this crucial step, we perform tests

and do experiments to see if our solution is workable. Here is where we weed

out those ideas that looked good on paper, but are unimplementable in the

real world. We can’t discover this until we try it. Be especially hard on

yourself in this phase; shooting down bad solutions is a vital part of the

creative problem-solving process. |

|

| Seven o’clock: Here is

where we document our solution and the tests and experiments we have

performed. This is how we are going to present our solution to the rest of

those involved, so we take the time and care to do a good job of it. If we

don’t write it up, we will have a harder time selling the idea, and things

that are not written down tend to fade quickly.

|

|

|

1

2

3 4

5

6

7 8

9

10

Write It Up

Back to Top |

|

1

2

3 4

5

6

7

8 910

Round and Round We Go

Back to Top

|

We’ve gotten the trial solution out, and enough time has gone

by for people to evaluate it. Now it is time to go through the loop again.

Here is what the six steps look like this time:

- Observe:

See how people are reacting to the trial solution. Have we made a dent?

|

|

- Listen:

Talk with people about the pluses and minuses of the solution. Get them to

tell us what they like and don’t like, what works and what doesn’t work.

|

|

- Empathize:

What factors could be influencing what we are hearing? Are people just

resistant to change? Is someone’s personal ox being gored by the solution?

Are there side-effects or unintended consequences that are causing people

grief? Or, is there "irrational exuberance?"

|

|

- Synthesize:

We need to take the new data and fold it back into the synthesizing process.

Can the original solution be tweaked, or does it need a major overhaul? Most

of the time we can go forward by modifying or improving on the last pass.

But we shouldn't be afraid to start our synthesis from scratch if we blew it

the first time.

|

|

- Try It Out:

With each pass through this station, we should become more intelligent about

how to test the solution. After all, we have the tests from the previous

pass, plus new data on what to look out for. Beat the solution up worse than

the critics will. Anticipate objections or problems, and see how the

solution performs when confronted by them.

|

|

-

Write It Up:

Using the original document as a starting point, modify what we need to, and

point out what we have changed and improved.

|

|

|

|

When are we done? Closure is important; we don’t want to

cycle through the loop forever. A good guideline is to stop when there is

very little significant new information obtained during the observing and listening

phases.

The process can begin at any point on the

circle. We must be opportunistic when it comes to problem solving. Real

life is “messy,” and sometimes the germ of an idea may come up, for example, through some

random synthesizing going on at the time. While it might seem better to stop

and go back to nine o’clock, sometimes the best thing to do is to seize the

moment and go forward from there. Don’t forget, we will always do at least

two complete cycles no matter where we start, so feedback is ensured.

That’s why that step at seven o’clock is so important – it’s what

precipitates the feedback. Note also a

very important beneficial side-effect: because we have been “writing it up”

as we go through the process loop two or more times, we don’t have a huge

documentation chore at the end. We will have progressively built up the

“final documentation” as an organic part of creating the solution in an

iterative way.

Solutions

obtained using this method tend to “stick.” The art is to navigate through

the six steps crisply and with all deliberate speed. Don’t skip steps, and don’t

get stuck too long on any one step. Once you gain experience with the

approach, you can improvise at will. But in the beginning, use the framework

to add discipline to your creativity. You may be surprised and pleased with

the results. |

1

2

3 4

5

6

7

8

910

Closure

Back to Top |

|

Back to Top |

Click here to e-mail Barbecue Joe on the Creative Problem-Solving Clock |

Back to Barbecue Joe |